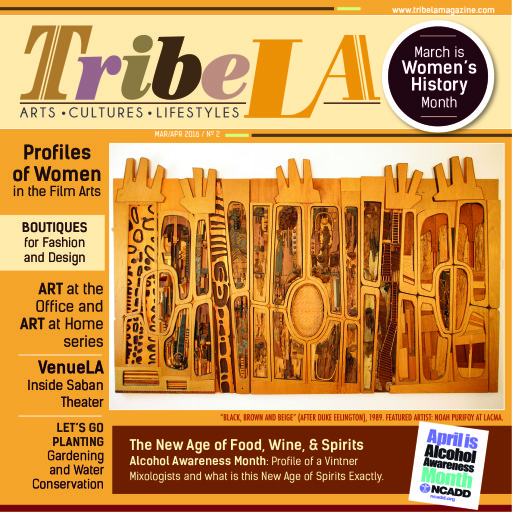

The first monographic exhibition dedicated to California-based artist Noah Purifoy

According to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada is arranged in loose chronological order, with an emphasis placed on distinct stylistic periods of Purifoy’s career. The artist’s landmark exhibition 66 Signs of Neon is represented through approximately one dozen assemblage works by Purifoy and other artists, including Judson Powell, Debby Brewer, and Arthur Secunda.

To Purifoy, the term assemblage referred to three-dimensional works that might serve as standalone sculptures (not as elements of an installation), and collage described two- dimensional works. Constructions were understood to be larger assemblages involving major elements of juxtaposed parts. Purifoy occasionally used the word combine to define both two-dimensional collages and three-dimensional assemblages, echoing a term coined by Robert Rauschenberg. Having developed this lexicon he continued to employ these diverse ways of working through the remainder of his career.

LACMA’s retrospective includes printed images from Purifoy’s 1971 solo exhibition at the Brockman Gallery. The artist referred to the provocative large-scale gallery installation depicting a single-room apartment inhabited by 11 family members as “environmental art.” Not long after this infamous exhibition, Purifoy withdrew from his art practice for over a decade, instead concentrating his energies on social work and as an arts advocate for the California Arts Council.

About Noah

Born in 1917 in Snow Hill, Alabama, and raised in Birmingham, Purifoy grew up in the segregated South 50 years before the effects of civil rights were tangible. During World War II, he served in the South Pacific in the then-segregated military as part of the US Navy’s Construction Battalion (Seabees). Following the war, Purifoy earned a master’s degree in social work in 1949 from Atlanta University in Georgia. He later made his way west, enrolling in Los Angeles’s preeminent art school, the Chouinard Art Institute, in 1951, where he became one of the first African American students.

His exposure at Chouinard (renamed the California Institute of the Arts, or CalArts, in 1961) to movements like Dada and artists such as Marcel Duchamp, as well as his subsequent work as a designer of high-end modern furnishings in Los Angeles’s flourishing mid- century furniture market, is evident in his body of work.

Purifoy went on to become an indelible part of the Watts community through his involvement with the Watts Towers Arts Center. There, among other things, he created art programs for underserved children. Relying on his social work training, he used art as a tool to inspire others. Though social work and artistic production were his life’s loves, he never practiced both simultaneously.

Purifoy soon became an important figure associated with the assemblage movement in Los Angeles, a group of artists that includes Melvin Edwards, Ed Kienholz, Llyn Foulkes, David Hammons, George Herms, John Outterbridge, and Alison and Betye Saar. These artists treated the urban landscape and its byproducts—what others might call “junk”—as materials for art.

Eventually, Purifoy was drawn to relocate to the California desert by the quality of light and the potential for solitary creation. There he created his magnum opus, the Joshua Tree Outdoor Museum. Bringing assemblage into dialogue with Land Art, the site embodies the totality of Purifoy’s vision, transporting his unique sensibility to the otherworldly landscape of the desert.