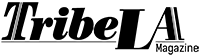

Mixed Remixed Festival: the nation’s largest gathering of mixed-race and multiracial families and people takes place at new venue: The Los Angeles Theatre Center

Creating the Mixed Experience

By HATTIE XU

“I am a story.” These four words, emblazoned on the shirts of volunteers at the 2016 annual Mixed Remixed Festival, proudly declare that each individual has a unique narrative, but they leave out the story of an emerging collective experience. Last year, the festival was set against the backdrop of historic Little Tokyo where members of a rapidly growing social and racial demographic – people in interracial relationships and people who identify as two or more races – come together every year to celebrate their stories. But while they all gather due to their respective mixed identities, they are united by a larger, underlying theme of creation.

For some interracial couples, acceptance of their family is the norm. In an area as diverse as Los Angeles County, with 72.2 percent of the population identifying as a minority, according to the 2010 U.S. Census, mixed relationships are common. In an arts and crafts room, Elliot and Aimee Jackson keep a careful eye on their daughter, who is playing intently with sequins and buttons, as they discuss the dynamics of their relationship. Elliot is Caucasian while Aimee has Filipino ancestry, and they share a smile when they say that race has not been a major issue for them, as the couple’s respective families readily accepted their relationship.

Though Aimee admits feeling a little out of place while visiting Elliot’s family in Minnesota – a state with 83.1 percent of the population identifying as white according to the 2010 U.S. Census, she says her own siblings are all in mixed relationships as well. “All of our friends have mixed kids,” Aimee says. “It’s a standard now.”

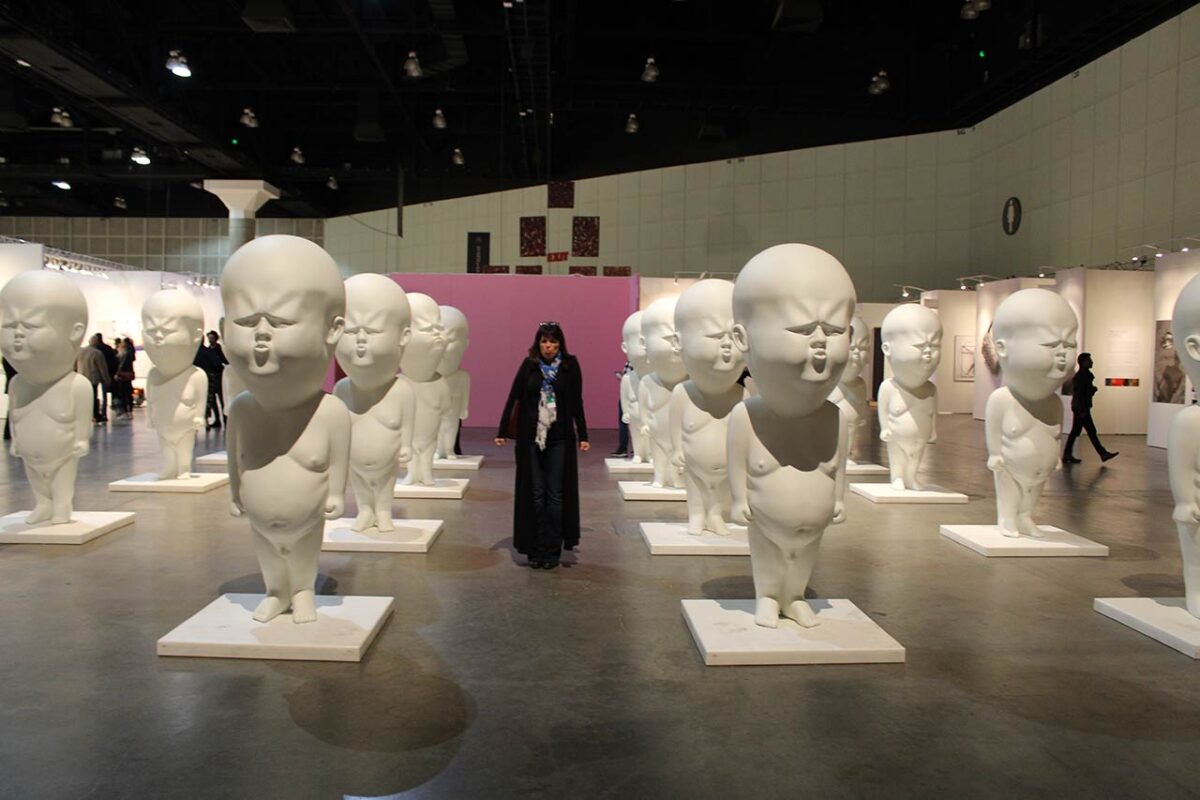

Mixed Remixed Film Festival

But outside of Los Angeles, attitudes towards mixed families can range from surprise – a double-take or strange look on an Oregon street – to outright rejection. Elizabeth Enslin, author and a panelist at last year’s festival on raising a mixed family, looks distinguished as she watches a group of children being entertained by a puppet show. With her tall stature and long, wavy grey hair, it isn’t a surprise to learn that she was once an anthropologist who worked in Nepal. Elizabeth’s story, however, is so unusual that it has inspired her to write several books about her experiences.

After marrying a man in Nepal and becoming pregnant, Elizabeth could see a clear fraction in the village where she lived. While many villagers supported and welcomed her – luckily, among them was her new mother-in-law – some village elders were against the interracial relationship and were vocal about it, even predicting that the child would be born with a birth defect. Her baby boy was healthy.

Elizabeth and her husband eventually divorced, and she and her son moved back to Oregon. Despite the geographic barriers, she has tried to raise her son with two cultures. Now in his twenties, he feels a strong connection to Nepal and has visited the village several times, learning the language and always wanting to do more to support his Nepalese family.

Against All Odds by Mildred Loving, Oil on Wood

For some, being one half of an interracial couple and raising a mixed family has been a learning experience more than anything. Cradling a baby boy with dark lashes and olive skin, Will Meyer acknowledges that he has had to “face a lot of things I didn’t have to think about as a white man,” such as paying more attention to the relationships between police and members of different racial communities. Sitting next to Will is his wife Crystal, a mixed-race woman with Caucasian and African American heritage.

Crystal recounts struggling with her own mixed identity while growing up in Koreatown. “You can be mixed, black, but not white,” Crystal says. “Back when I was in school, you couldn’t check two boxes. It didn’t feel honest to mark ‘black,’ but I knew people wouldn’t let me mark ‘white.’”

Raised by a white mother, she didn’t understand why black classmates – some of whom once tried to cut off her hair – were angry at her. Crystal wishes she realized then that they were angry because they didn’t think she understood the struggles that black people face, believing that she was more privileged with her white upbringing, lighter skin tone, and more relaxed hair. They were even angrier that she didn’t know why they were upset.

Stroking the face of his sleeping baby, Will says he isn’t sure how his son’s mixed background will affect his life and how he will grow up, but he has a wish for his child that many parents share. “I hope he can be himself.”

Just by looking around the festival, it is clear that the event has brought people together and forged friendships. At the glass doors of the main entrance, a group of women – some dressed in suits and others in loud, colorful prints – talk animatedly. At the bottom of the steps, two men eating bagged lunches catch up and survey the scene around them.

These two men are Chris Terry and Aaron Samuels, who are both mixed-race writers that have participated in every Mixed Remixed Festival since its inception in 2008. Last year, they were panelists in a conversation on code switching, which are the “changes that we make to our affect or language that give us access to different spaces,” defines Aaron, who has Jewish-American and African-American heritage. For example, one might subconsciously – or completely consciously – use more stereotypically “black” speech around other black people and more stereotypically “white” speech in the workplace in an effort to avoid discrimination, explains Chris, who has Irish-American and African-American heritage.

As Chris and Aaron learned to come to terms with aspects of the mixed identity – such as not knowing how they are being perceived or “rooms changing” when people discover that they are half black or half white – they have found the importance in seeking out spaces where the mixed experience is supported. Through Mixed Remixed and other personal projects, Terry and Samuels are helping build spaces for the mixed voice, using their creative voices to share their stories, and empowering an entire growing community.

These are just a few members of the multicultural community in Los Angeles, and together they are powerful. Mixed relationships are creating interracial families and mixed children, who are establishing their own support systems and outlets of expression. This is where modern America is slowly headed – not a society that doesn’t see race, but one that sees all, seeks to understand all, and accepts all.

Globalization and multiculturalism is not just foreign policy or trendy fusion restaurants; for a growing number of people, it is in their DNA. Reconciling two cultures can be nearly effortless, but for most it takes years of introspection and struggle to find a balance that works. All mixed relationships and individuals are the sum of its parts, and this collective mixed experience of accepting two cultures, learning to connect these puzzle pieces, and creating a cohesive identity is what binds these individuals together.

Mixed Remixed Festival

Though I am ethnically full Chinese, the mixed experience resonates with me. From the food I eat to the epicanthic folds over my eyes, being Chinese is indisputably a part of me, but the media I consume, the language I think in, and the nation I support in the Olympics might suggest otherwise. Yet to white America, I will always be hyphen-American, and to the Chinese, I will always be too whitewashed to call one of their own.

Whether it is a family or a space to tell a story, what is being created by this community is their identity – the mixed identity. I’m encouraged by the strength of this community and motivated to pursue my own voice that cannot be confined to one box.

Festival link update for 2017: Updates & News – Mixed Remixed Festival